RPE: Fitspo Jargon Or Training Epiphany?

Over the past decade the argument between autoregulation and percentage based programming has been rife within the lifting community and on gym floors across the globe. The term ‘RPE’ is often used in programming that uses autoregulation. This article aims to shed light on what RPE is, where it came from, how it has evolved, where it stands in the battle against percentage based programming and ultimately our best practice method available to draw upon for autoregulation based training.

01. What is RPE and where does it come from?

The term RPE stands for Rate of Perceived Exertion and is a method of measuring exercise intensity. The concept was initially discussed by strength and conditioning coaches in the 1950’s and then formally popularised by Gunnar Borg in ’62 with his ‘6–20’ scale which was primarily designed for aerobic style training. Borg later introduced the ‘CR10’ and ‘0–10 RPE’ scale you are most likely more familiar with shown in figure 1 below.

Figure 1

This method has evolved and been adapted by coaches around the world through execution across different disciplines. As the title of this article may suggest, we are most interested in the application of RPE to performance based training and weight training in particular. STCfit specialises in body composition, general strength, physique and powerlifting training therefore our conversation moving forward will be centred around achieving those outcomes using the RPE method.

One of the most common adaptations of the RPE Scale came from Mike Tuchscherer of Reactive Training Systems when in the attempt to further define the rating (due to some numbers left blank therefore making the system feel vague), he introduced the concept of reps remaining. The idea started by clarifying the definition of RPE10 as maximal effort and essentially meaning it was a ‘rep max’. A rep max can be further defined by simply saying, “No extra reps would be possible at the prescribed reps with that weight.” Mike reverse engineered this concept and we ended up with ‘9 = 1 more rep possible, 8 = 2 more reps possible etc. He even refined it further by adding a decimal to represent maybe “X” more reps possible (eg. 9.5 = maybe 1 more rep possible).

Figure 2 - reactivetrainingsystems.com

Now … It is very common to see a program that lists sets, reps, and RPE.

Eg. 4 sets of 5 @ 8 RPE

To break this down, the person completing the program would perform 4 sets of 5 reps at a weight that would allow them to complete 7 reps if required.

02. Introducing RIR?

The above approach ultimately led to the term ‘RIR’ or Reps in Reserve, perhaps made most popular by Mike Isratel of Renaissance Periodisation. With RIR, we simply count upwards to estimate how many reps you had left ‘in the tank’. 0RIR being a max effort, 1RIR being 1 left in reserve and so on.

The goal of switching to RIR is to simplify the process for a client. It’s one less step to take (“I could have only done one more” = 1, rather than converting to RPE 9). For clients that are unfamiliar with the history we’ve just explained, it’s a much easier system to digest.

The above example could then be shown as 4 sets of 5 reps @ 2RIR, ultimately translating to the same perceived difficulty.

Now that we understand how RIR came to exist, we can explore the pros and cons of the concept as a programming strategy.

When discussing the pros and cons of RIR, we need a controlled variable to compare it to. We’re going to use two; The %1RM method and no prescription at all.

What is the %1RM Method?

The % 1 Rep Max method is one in which the lifter either tests their 1RM, or calculates it using a formula using max repetitions of a set weight, or max weight for set repetitions.

The results are then loaded into a program where further results are populated and then prescribed as a % of the 1RM depending on target outcomes and reps.

Typical guidelines for the %1RM method look like this:

Figure 3

This method has been used by strength coaches for close to a century and is often referred to as the gold standard of load prescriptions.

Considerations

Variables that are impacted by selecting a particular method are:

Accuracy

Autoregulation

Skill and strength adaptations

Lifter personality

Accuracy

RIR

The study, “A novel scale to assess resistance-exercise effort. Hackett DA1, Johnson NA, Halaki M, Chow CM,” concluded subjectively that the method ‘Reps Remaining’ was at worst 93% accurate, and that the more sets done using the method, the greater the accuracy. Perhaps indicating frequent use of this method allows for greater assumed accuracy.

%1RM

It is assumed that using the %1RM method is the gold standard when it comes to prescribing intensity. A consideration around this idea is that 1RM testing is only realistically applicable to compound lifts and as a result potentially leaves a hole in programming loads for accessories. Typically the solution for this would be a prediction based model where a formula is used to predict a 1RM based on a higher rep set taken to max effort.

“Predicting Maximal Strength In Trained Postmenopausal Woman. Wolfgang K. Kemmler, 1 Dirk Lauber, 2 Alfred Wassermann, 3 And Jerry L. Mayhew 4”, revealed the predictive model to be within around 3% accuracy. Another consideration is the ever changing skill proficiency and strength of a lifter. This is due to training age and/or exercise prescription changes meaning the strength a lifter is able to express increases each week of the program, even if potential strength does not change.

No prescription

With no measurement of intensity, objective or subjective, we are unable to determine the effort required to perform a set. This may be suitable for a beginner who is simply going to “do more each week”, but may still cause complications when it comes to considerations of volume load and recovery over a program.

Autoregulation

RIR

One of the primary reasons for using RIR is to provide Autoregulation. “RPE vs. Percentage 1RM Loading in Periodized Programs Matched for Sets and Repetitions

Eric R. Helms1*, Ryan K. Byrnes2, Daniel M. Cooke2, Michael H. Haischer2, Joseph P. Carzoli2, Trevor K. Johnson2, Matthew R. Cross1, John B. Cronin1,3, Adam G. Storey1 and Michael C. Zourdos2”, discussed the argument that autoregulation based training could in fact be superior for strength progress when compared to % based training.

There are many other considerations for the lifter and/or coach that aren’t mentioned in such studies. Autoregulation allows the lifter to select load based on their performance capacity of that day. This daily performance capacity can vary based on many recovery factors such as sleep, nutrition, lifestyle stress and the program itself. Seeing a dip in load shifted at the same RIR is cause for discussion and/or the review of other data points.

%1RM

Expressions of a reduction in training performance capacity while following a %1RM model will still be expressed, however it’s reliant on vague feedback (eg. “It felt hard today”), or simply watching the lift and judging how hard it looked by technique, skill expression and speed. This could potentially lead to training the lifter closer to failure than planned and as a result creating more fatigue. This then triggers a downward spiral of performance capacity due to their decreased recovery status. In the worst case scenario, we see a lift taken beyond failure to a missed lift and in the example of a deadlift, could require upto 14 days for full recovery as is common practice in powerlifting peaks.

With this knowledge we can zoom the lense out to a 6 month training cycle and consider the amount of time spent in recovery phases (deloads) vs progressive overload. It’s reasonable to assume over a 6 month autoregulated training cycle that the lifter would spend more time recovering from more “work” as opposed to the %1RM group.

No prescription

As previously mentioned, without an intensity prescription it is unclear as to what a lifter will do. Perhaps they will autoregulate based on how they feel and perhaps they will over reach recovery capacity. Not knowing about these factors leaves us in the dark when making informed decisions on programming and lifestyle factors.

What about speed?

Before we move on, it’s important to note studies that practice autoregulation through assessment of bar speed have shown promise to be more effective than RIR. I have chosen to leave this out for a couple of reasons;

To achieve best results, a personal profile should be created for each lifter and their bar speed at different loads and different lifts.

The equipment required to measure bar speed accurately is expensive, inconvenient and not suitable for most coaches.

Frequency of Performance Increase (Skill and Strength Adaptations)

To discuss this segment, I’m calling more upon anecdotal experience as there is limited research due to the complexity required to effectively study these topics.

RIR

A leading discussion point around RIR vs %1RM methods tend to be driven by the question, “Who is the programming for”? Some would suggest beginners and others would suggest everyone. Personally, I’ve been using autoregulation in my programs for around 4 years. I work with clients ranging from beginner to intermediate lifters, clients with general strength and body composition goals to powerlifting and bodybuilding outcomes.

I believe the best use for comparison are the 100 powerlifting preps we’ve programmed using a variety of autoregulation strategies (discussed later under “What Were the Outcomes”).

The main thing I’ve noticed across all of these programs, is the ability for a lifter to change characteristics throughout a meso cycle. The three most notable are; confidence, skill and strength. The more confident the lifter becomes, the more likely they are to express their strength potential. The more skilled they become at a movement, the more they express their strength potential. Basic adaptation to training compounds these two (confidence and skill) with increases in expressed strength. This has shown to be true in international level lifters as well as more obvious beginners.

Using an RIR method allows for the client to progress in load at the speed of their progression, not to that of a load prescription.

%1RM

Taking into consideration the potential for weekly differences in 1RM, the argument for accuracy using this method would suggest the need to retest frequently. The unfortunate reality is that testing comes with fatigue and therefore the goal of ‘most work done in a 6 month cycle’ would pose counterproductive to using this approach.

A typical management tool here would be to select a predetermined weight increase each week and assess performance and feedback. This has shown to be anecdotally effective for many lifters.

No prescription

Given the lack of clarity and ability to accurately measure progress, no prescription may be able to take advantage of frequent performance increases. Typical human behaviour would suggest a lifter would attempt to better themselves each week, thus capitalising on any new found performance.

Lifter’s personality

RIR

Perhaps the biggest drawback of the RIR model is managing individual approaches to training. RIR9 might actually be an 11 with technique and skill breakdown for the ego lifter, or 6 for the over-thinker. This would require more feedback and education from the coach, sometimes telling white lies in the prescriptions or suggesting weights in the following weeks, thus removing the ‘auto’ in autoregulation.

%1RM

As one may have already gathered, RIR’s biggest weakness is %1RM’s biggest strength. Lift the weight prescribed. Lifters may still veer off course however it is a clear deviation rather than ‘misinterpretation’.

No prescription

Similar to that of RIR, no prescription may cause training too close to fatigue and too often resulting in limited progress, increased injuries, underperformance and failing to reach intensities required to progress.

Summary of considerations

Taking all of the above into account, we can better understand the complexity and back and forth nature of the argument. Despite an openly biased lense as a coach and lifter who uses RIR, there are clear benefits to a percentage method.

A profound conclusion at this stage of discussion is the clear advantage to using some style of method that measures and tracks the load a lifter is using. Anyone looking to achieve results by any means should be using a prescription method.

To properly conclude this discussion, we now need to look into finding a best practice method.

05. Best Practice

Having implemented an autoregulation method for multiple years, it was typical for us to prescribe the following week’s working weight based on what we had seen or felt during the current week’s training. This is a subjective style of prescribing load while adapting elements of a percentage model. Despite being effective for some aspects, it didn’t bode as well for application to an entire program. This is particularly true for online coaching as well as being less user friendly for a beginner coach or lifter.

To settle on a system which could be considered best practice we would need to further refine the method. The goal of any systemised approach is to remove as much human error as possible.

The functionality we needed included:

An objective weight prescription to create as little “wasted” sets and/or weeks in a program as possible.

A subjective variable which would allow the client to autoregulate session to session, allowing them to outperform an algorithm if progress permits, or to display data on under recovery to prompt further investigation.

The ability to use RIR as a method of micro cycle load periodisation.

Finding the formula

A resource we came across (Quantifying Hypertrophic Reps And Hypertrophic Volume Load by James Kreiger) at Weightology provided a wealth of valuable information which directly impacted our proposed programming model in 3 ways.

The Brzycki equation; a method in which to predict a 1RM. Upon further investigation, this method has shown to be effective in literature such as ‘Validation of the Brzycki Equation’ for the estimation of a 1RM in the bench press. Matheus Amarante do Nascimento1, Edilson Serpeloni Cyrino1, Fábio Yuzo Nakamura1, Marcelo Romanzini1, Humberto José Cardoso Pianca1 and Marcos Roberto Queiróga2

Kreiger had refined the equation to include consideration to RIR, a game changer for our proposed application.

The Hypertrophic Reps concept added more validity to the RIR/RPE periodisation model presented by Mike Isratel and Chad Wesley Smith in ‘Scientific Principles Of Strength Training.’

The Formula

Prescribed load = Previous load * (36/(37-((previous reps -prescribed reps) + (previous RIR — prescribed RIR+1)))

The Application

Upon looking at the formula, there were two considerations that needed addressing before creating a method.

We needed a previous load, reps and RIR to consider.

There were three different methods of predicting a 1RM. All methods returned significantly different predictions thus concluding inaccuracy.

Creating a Standard

As previously discussed, we were ideally looking for a method we could apply across an entire program, not just to the compound lifts. This meant we needed to create a previous load, rep and RIR standard.

We decided upon two options.

A testing week — the client would perform one top set of each exercise at a similar rep range to that of the future prescription of the program. We chose to apply 1RIR to minimise and balance fatigue levels where possible. Two happy coincidences came from the testing week method.

It adhered to the principles of a delaod (keeping intensity high while reducing the volume) making it a great ongoing strategy.

It provided an introductory week to the program with sub maximal sets to improve skill execution of new movement patterns introduced in a new macro cycle.

In certain cases where there are time restrictions due to a training outcome deadline or an inability to perform exercises at high intensity due to execution proficiency, it was better to skip the testing week and allow the lifter to ‘find’ the prescribed RIR in week one of a meso cycle.

Allow for Human Error

No algorithm is ever going to be perfect. Two lifters will never have the same performance capacity and in fact an individual lifter’s performance capacity will vary each micro, meso, block and beyond. Adding this to an imperfect formula means we must allow for self correction.

Our method was then set up to allow for such events. The lifter would have a prescribed RIR, a predicted weight and an actual RIR.

The lifter is instructed to complete their first working set with the predicted weight, then compare their subjective RIR with the prescribed RIR and adjust the weight accordingly repeating for all sets. The client would then enter their actual RIR based on their hardest or heaviest set. This data would then be used to predict the following weeks load using the new prescribed RIR.

An important note to make here is that the nature of this equation is going to result in unrealistic weight selections sometimes with weird decimal plates. To rectify this, we will need to round to the nearest 2.5kg progression.

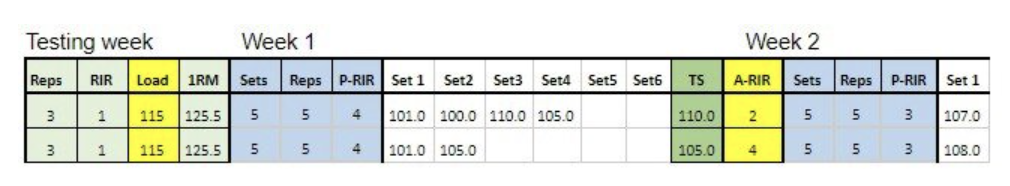

Eg.

Jim has 5 x 5 @ RIR 4 predicted at 100kg

Jim performs set 1 & 2 at 100kg and decides its a 5RIR

He jumps to 110, which felt a 2RIR

He backs off to 105 and feels confident it’s a 4RIR

He enters Actual RIR as 2 based on his heaviest set (TS = Top Set).

Next week is a Prescribed 3RIR, resulting in prediction of 107.5kg

To confirm this method’s accuracy, we can see what happens if we do the math based on the 105 at 4RIR. As it turns out, it returns a prediction for 108 the following week.

Rounding 107 and 108 to the nearest 2.5kg progression = 107.5 in both scenarios.

Shown below in Figure 4:

Figure 4

The Formulas:

1RM

= load * (36/(37-(Reps — RIR))

Eg: 1RM = 115*(36/(37-(3–1))

Set 1 Week 1

= Testing Week Load * (36/(37((testing week reps — week 1 reps) + (testing RIR — week 1 prescribed RIR + 1)

Eg: Week 1 Set 1 = 115*(36/(37-((3–5)+(1–4+1)))) = 101 rounded to nearest 2.5kg = 100

Top Set (TS)

= MAX (Set 1 : Set 6)

Set 1 Week 2

= Top Set * (36/(37((week 1 reps — week 2 reps) + (week 1 RIR — week 2 Prescribed RIR +1)

Eg. Week 2 Set One = 110*(36/37((5–5)+(4–3+1)))

There were many extra box’s this approach ticked for us when it came to programing;

Easy to spreadsheet

Repeatable and refined enough for beginner coaches to utilise as a system

Allowed for gender / fibre type dominance / fitness and other variables that would affect a lifters ability to repeat effort

It could be measured and reviewed weekly

Very strong performance outcome data could be attained when tracking lifestyle factors and nutrition along with RIR

Some issues we ran into;

Assisted exercises like dips and pull ups were complicated to enter

Some exercises need to be progressed via reps not load

Human error during and after testing week

Overall we feel we’ve found the closest thing we can right now to a systematic, quantifiable approach to autoregulation based training, though we expect it will evolve with new evidence both in practice and in the research.

What Were the Outcomes?

The biggest test of this method was the debut of our Powerlifting team at the 2020 APU Melbourne Open. We’d previously run 5 mock meets for clients and had representatives medal 2019 in local, state and national meets in both APU and GPC.

All our lifters used this method and all with a short announcement to comp having a 12 week prep time where the majority previously had a 13 week turn around from their previous meet.

We had 4 coaches ranging from coaching their first comp up to their 9th.

The teams results were as follows:

Figure 5

We were extremely proud of the outcomes.

Paying specific attention to the RIR strategy we noticed the following positives;

Weekly prescriptions of top sets were accurate 95% of the time.

Weekly management for the coach was focused more on the athlete and less on the numbers.

Accuracy was consistently good through hypertrophy, hybrid and strength phases.

Due to time restraints a mixture of using and not using testing weeks was implemented. We often used top sets of higher rep ranges from previous phases as week one predictions which proved to be effective.

Cons we experienced were all in the peaking phase. Lifts more often that not needed to be visually seen, discussed and then prescribed for the following week.

We noticed the more experienced the lifter, the less often this tended to happen. There were some missed lifts which most often were due to a lack of confidence from the lifter however there are two interventions that could have solved this problem.

A discussion with the coach: If an athlete expresses a lack of confidence to hit a number, it’s unlikely a coach will put them under that load unless a conversation is had to build reassurance.

RIR examined during warm up sets: If fatigue has built to a point where the predicted weight isn’t achievable, it’s likely to be felt during the sets leading up to the attempt. Some athletes became too focused on the number prescribed and were unwilling to ‘settle’ for a lesser weight based on their prescribed RIR.

The data allowed us to build a profile of the physical characteristics of the lifters and also built a profile of their personal tendencies in application. This allows us to modify prescriptions and/or re-educate the lifter for our next prep.

Summary

As with all things fitness and particularly true for programming, there are many valid methods. What’s most important is to have a deeper understanding of the principles allowing you to be fluid and educated with the method you chose.

The above discussed approach will be our baseline systemised method however it is not cut and dry. Adjustments and refinements will need to be made for individuals and circumstances.

In future articles we’ll dig deeper into programming principles, including volume landmarks with consideration to intensity, proximity of failure and exercise selection.

Lift smart, lift hard, lift long.

Research Papers

Novel Resistance Training–Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve

Zourdos, Michael C.1; Klemp, Alex1; Dolan, Chad1; Quiles, Justin M.1; Schau, Kyle A.1; Jo, Edward2; Helms, Eric3; Esgro, Ben4; Duncan, Scott5; Garcia Merino, Sonia6; Blanco, Rocky1

Session-RPE Method for Training Load Monitoring: Validity, Ecological Usefulness, and Influencing Factors

Monoem Haddad,1,* Georgios Stylianides,2 Leo Djaoui,3 Alexandre Dellal,4 and Karim Chamari5

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5673663/#B6

Application of the Repetitions in Reserve-Based Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale for Resistance Training

Eric R. Helms, MS, CSCS,corresponding author1,*John Cronin, PhD, CSCS,1,2,*Adam Storey, PhD,1,*and Michael C. Zourdos, PhD, CSCS3,*

Monitoring Editor: Brad Schoenfeld, PhD, CSCS,CSPS, NSCA-CPT

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4961270/

Beginning RTS

November 29, 2015 RTS Basics, Training Tactics Mike Tuchscherer

https://articles.reactivetrainingsystems.com/2015/11/29/beginning-rts/

RPE and Velocity Relationships for the Back Squat, Bench Press, and Deadlift in Powerlifters

Helms, Eric R.; Storey, Adam; Cross, Matt R.; Brown, Scott R.; Lenetsky, Seth; Ramsay, Hamish; Dillen, Carolina; Zourdos, Michael C.

Validation of the Brzycki equation for the estimation of 1-RM in the Bench Press

Matheus Amarante do Nascimento1, Edilson Serpeloni Cyrino1, Fábio Yuzo Nakamura1, Marcelo Romanzini1, Humberto José Cardoso Pianca1 and Marcos Roberto Queiróga2

http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbme/v13n1/en_11.pdf

Weightology — QUANTIFYING HYPERTROPHIC REPS AND HYPERTROPHIC VOLUME LOAD

Scientific Principles Of Strength Training https://www.jtsstrength.com/product/scientific-principles-of-